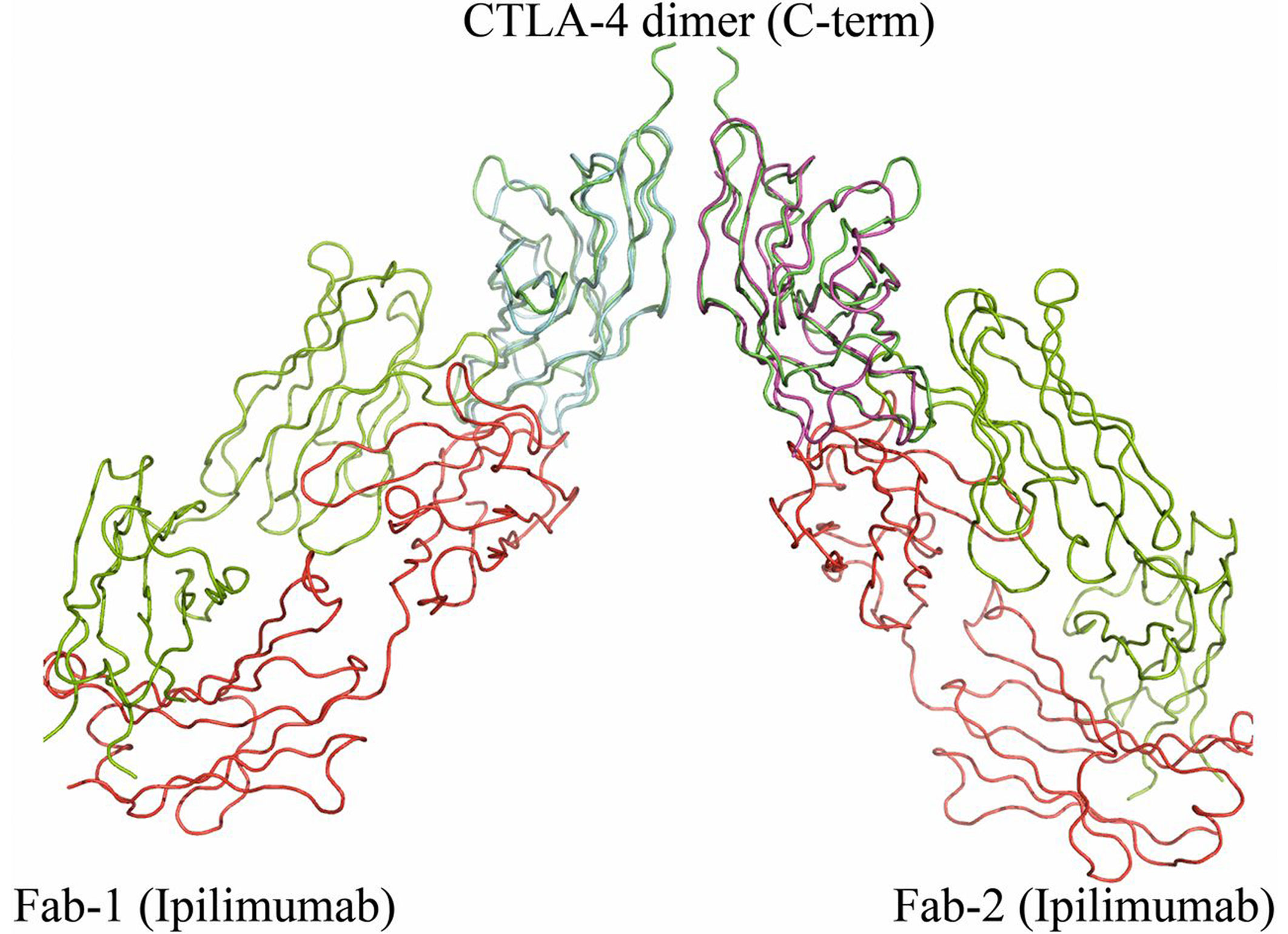

Ipilimumab (now branded as Yervoy), which is based on the research of Noble Laureate James Allison, is the first-in-class immunotherapeutic for blockade of CTLA-4 and significantly benefits overall survival of patients with metastatic melanoma.

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]hen I was a sophomore in college, I was diagnosed with melanoma, an aggressive form of cancer. Within 24 hours, I was on a plane home, and 24 hours after that I had surgery to remove the tumor.

That initial whirlwind of activity stood in stark contrast to what happened next: nothing. As my doctors explained, melanoma doesn’t respond to chemotherapy, radiation, or any other therapy they had to offer. After surgery, my only option was to wait and hope the cancer didn’t come back.

But it did. Three months later I found a lump in my neck. The disease had returned and progressed to stage IIIc. At age 20, survival statistics gave me a 40% chance of making it past my 25th birthday.

However, those statistics couldn’t account for a groundbreaking development during the brief window before my cancer returned. Just weeks before I found the new tumor in my neck, a team of researchers published a paper revealing that a drug called ipilimumab improved survival in patients with advanced melanoma. For the first time, oncologists could offer melanoma patients a pharmaceutical therapy.

Although ipilimumab (which is now branded as Yervoy) wasn’t approved until the next year, I was able to access the drug through a clinical trial – a development that very well may have saved my life. Had I not received the drug, there’s a one-in-five chance that I wouldn’t be here writing these words today, according to the study’s results.

The movie-like appearance of ipilimumab in my life was the culmination of a multi-decade process that started when I was a toddler. The drug’s development is rooted in university research James Allison performed in the early 1990s. (Allison shared The Nobel Prize for Physiology and Medicine 2018 for that work.)

Most accounts of ipilimumab’s development fast forward to the successful large-scale trial that led to its FDA approval, overlooking the decade and a half of heavy lifting that is typically required to develop a life-saving drug. Researchers like Allison need to find a corporate home for their breakthroughs (or build one themselves.) They also need to raise capital and negotiate licenses before they can even begin to solve manufacturing challenges and run clinical trials.

These are formidable challenges. Allison told NPR that he was “depressed” by his initial failure to find a company willing to commercialize his research. Fortunately, he worked at Berkeley, in the middle of a major technology startup hub, where he was surrounded by the resources required to overcome those challenges.

Because I survived cancer, I was able to finish my degree in math at Yale, and I went on to work at the Boston Consulting Group and then Google. I’m married now, and I’m able to support my wife as she trains to be an oncologist. (This frequently takes the form of sending her pictures of our dog and cats while she’s working in the hospital.)

Unlike my wife, I don’t expect to work directly with cancer patients. But as the lead data scientist for Research Bridge Partners, I’m doing my part to identify and commercialize breakthrough treatments. Our non-profit has built a one-of-a-kind data model that lets us search for future James Allisons – only those who don’t happen to be next door to Silicon Valley. We use data to find the researchers whose science could save lives, but who might not get the chance to do so because they work in the wrong part of the country.

We use a lot of math and a lot of domain expertise to find these men and women. Then we do our best to ensure that the science behind the next ipilimumab gets bridged to the resources and people who can turn it into Yervoy-calibre impact in the lives of patients – like me – throughout the world.